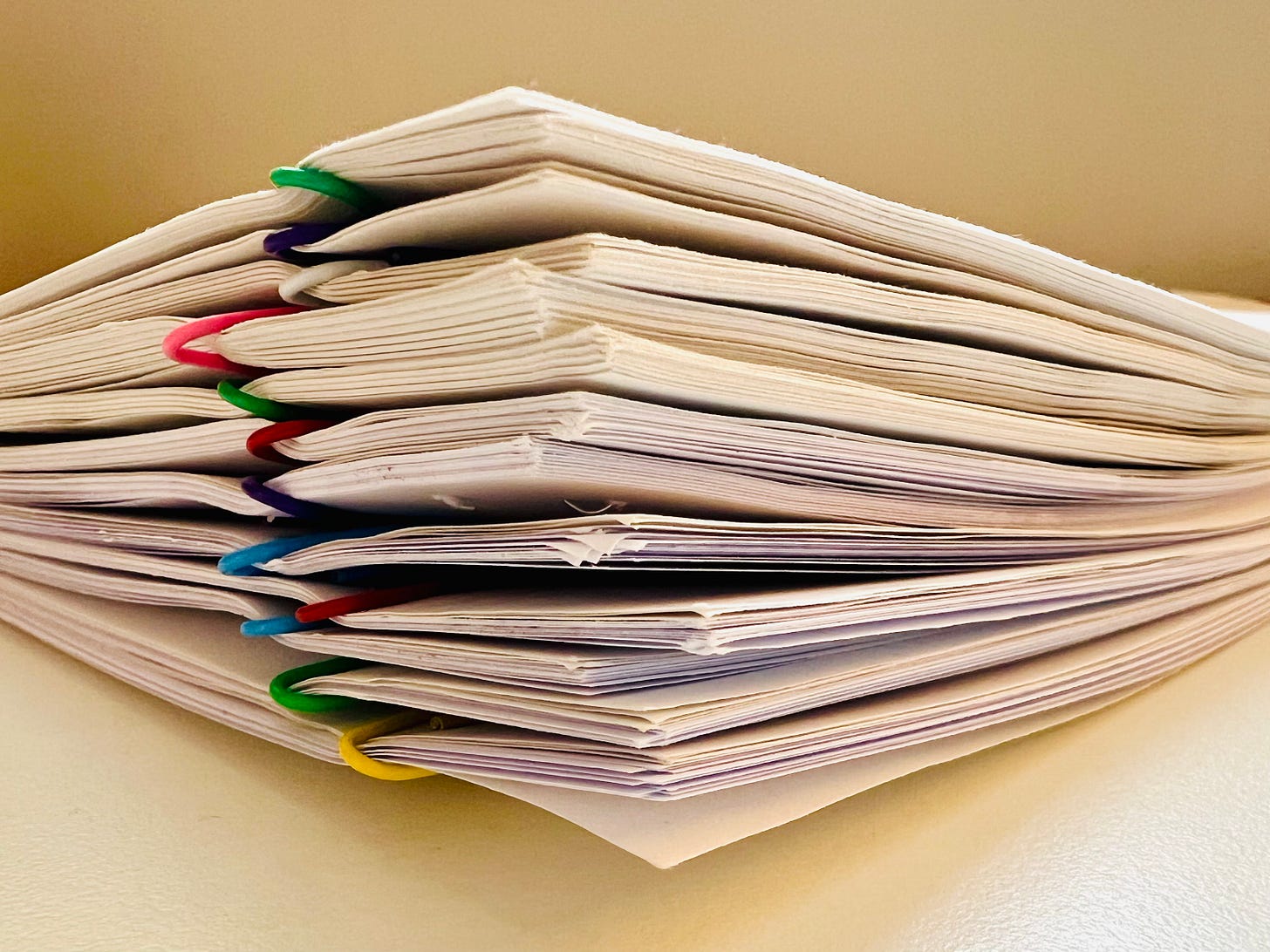

Twelve chapters, 60,000 words—completed on May 28, 2025. That’s Draft Eight of my novel-in-progress.

I can’t even remember when I started it. But I know when I’ll start Draft Nine: next week.

Why the rush? Because Draft Nine will be the final draft. I feel the end coming, and it feels good.

When I began Draft Seven, I wrote a short Substack post about my process when I write novels. (TL;DR: it gets fun only in the later drafts). The later the draft, the funner it gets, because most (though not all) of the structural work is done. The craft considerations, about which I’ve also posted before, become subtle. I get to put the final touches that make the story breathe to life.

The final draft is the one in which, years after beginning the novel, I finally get to play. And the material I’ll be playing with is, of course, language—in all its elasticity.

To write about non-English subjects in English is to translate; that was the argument I made in my Master’s thesis in English. This is still how I approach my creative practice today. Translating and writing are equal parts of the same act for me: I write about Nepal in English, and I also translate Nepali literature into English.

Which is why I’m inspired by the process of translators as much as that of writers. Recently, I read an interview of International Booker Prize winner Banu Mushtaq’s translator Deepa Bhasthi in Scroll. You can read the full article here, but this is the extract that resonated with me:

“…The aim of translation, especially in former colonies like ours where English is acquired along with a complicated baggage, should never be to write in “proper” English. When one translates, the aim is to introduce the reader to new words, in this case, Kannada or to new thoughts that come loaded with the hum of another language. I call it translating with an accent, which reminds the reader that they are reading a work set in another culture….”

Yes, exactly.

So in the final revision of my novel-in-progress, I’ll be stretching and molding and shaping the English language to find the pitch of my first-person narrator’s voice. I’ll imprint the Nepali language onto English, yes, but in ways that serve her personal voice. You know how all of us have an inner voice, one that speaks in staccato rhythms, in broken sentences, in half-formed, flyaway fragments? I’ll be bringing those to the page in the final draft.

What fun.

Before I get to that part, though, I’ll begin with a less fun but necessary errand: to check on the story arcs of all the characters—primary and secondary and tertiary and also fleeting background figures—to make sure that I’ve resolved each adequately.

This is the thing about writing a novel: there’s always structural work to do, from the very start right up to the end.

Always enjoy reading about “how the sausage is made”, and am so looking forward to your next novel. I am sure it will be worth the wait.